Chapter 3

In this section we will explain the concept behind the ideas of frames and reframing. We will draw on lots of thinking and practice, but try to keep it accessible.

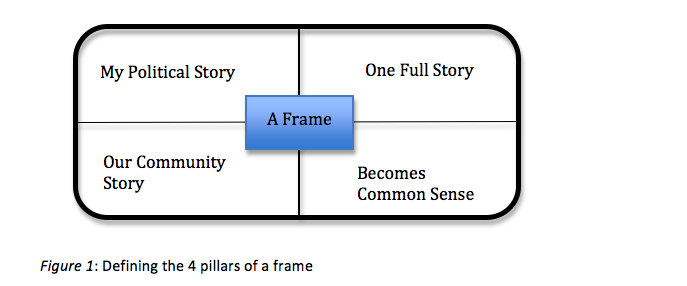

Frames are the stories that explain and drive our political thinking

At the core of our toolkit is the concept of frames. There are key aspects of frames that are important to understand for the campaigner is as follows:

My political story

Put simply, frames are stories we use to understand complex and challenging issues in life like migration or climate change. When a new issue becomes part of the public discussion, we tune into mainstream and social media, talk it though with friends and normally guided by our values and political affiliations, we adopt a certain position or frame on the issue.

One full story

A frame is a full story that covers the nature of the problem, what’s the cause, who are the good guys and who is to blame and the possible solutions. Of course, it is just one story in many possible ways of interpreting and evaluating an issue[1].

Community stories

Once we commit to a single frame, we make it our go-to understanding on the issue and over time these frames also become highly valued stories in our political ‘tribe’.

Becomes Common sense

This makes our attachment to them even stronger to the point they actually become part of our ‘cognitive unconscious’, making these stories our ‘common sense’ and so very easily triggered by a picture, a word or phrase, a metaphor or story[2].

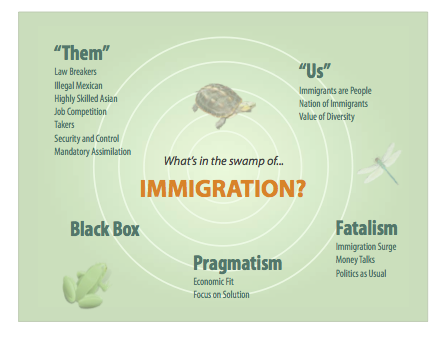

To illustrate, the Frameworks Institute recently mapped out the core frames (pro & anti) in the immigration reform debate in the USA[4]:

Examples of Frames in the toolkit cases:

National Level: Poppy Hijab Campaign, British Future, UK (link to the descriptor)

To challenge anti-Muslim sentiment, British Future developed a more patriotic frame around the slogan “Proudly British – Proudly Muslim” that commemorated the 400,000 Muslim soldiers who died fighting in the first world war for Britain.

Local Level: Shrewsbury Mosque, Hope not hate, UK (link to the descriptor)

To challenge an othering anti-Muslim frame from those opposed to the building of a Mosque in the town, Hope not Hate? Changed the discussion to a ‘right to worship’ frame and got local community church leaders on board to deliver the message.

People are more frame-driven, than fact-driven

As we said above, frames are not just stories to help individuals understand complexity, they are also socialised stories that become valued in particular political groups in society[5]. In this logic, challenging these frames that have such a strong attachment is not just a rational argument about the facts, but also somewhat a challenge to identity and so often an emotional response[6].

This may explain why progressives get dismissive and angry responses, when they argue facts and rights only in the migration debate, i.e. these arguments often don’t connect to the frames and concerns expressed by the public in this debate. We are not arguing for you to adopt their positions, but at least to connect and acknowledge them (see the how to engage section).

Mythbusting has limited efficacy in a heightened debate such as migration

Given the fact that individuals have strong ownership of their existing frames, it is not surprising then that people often process new information in a way to support their existing opinions[7]. And when we push even harder to change their views, they can get even more attached to their existing positions – this is called the backfire effect[8]. Experience of such backfiring has been reported in discussions of migration in the UK[9].

There is an understandable tendency in this debate for both sides to get highly emotional and to try to prove people wrong. “However, such myth-busting has little efficacy in broader public debate, if it is aiming to do more than raise the morale of those who already reject the myths”[10]. Lakoff argues that liberals often stress facts and rationality without explaining what the moral importance of the facts, i.e. facts in story that contextualise the reason they matter work much better[11] (see that what to say section).

Dominant frames are very effective in limiting/focusing public opinions of any issue

Frames inherently focus on some elements of issues and ignore others. In the current refugee crisis in Hungary, in a state controlled media space, the frame of invasion, security, protection from the outsider dominates and in most polls show is widely held. According to the literature, a single dominant frame in the media will indeed lead the debate and sets the public agenda[12]. This is a significant issue for those wishing to start and lead a different discussion.

Some argue that frames mostly start from the top and with the blessing of elite opinion leaders and media, the story cascades down the various steps of multiple communication outlets to the population, while others have a more democratic view, and see the process involving more of a bottom up approach from stakeholder groups and elected representatives bringing frames to the table[13].

Frames that are ‘sticky’/resonant, coherent and accessible, brought to us from trusted sources and are repeated a lot have a very good chance becoming a competitor with other frames or eventually even the dominant story in a political issue[14].

Once the there is a dominant media frame or a small number of competing frames, they become the so-called ‘tidy media narrative’– setting expected elements and actors in any story on the issue. Once this happens, the hold of these dominant frames is difficult to break and introducing something completely new, you risk getting seen as not relevant or your input only coming down the end of a column, i.e. in serious risk of being editing out![15]

As any advocacy manual will tell you, reframing or countering dominant frames takes significant effort, persistence, creativity, all kinds of support from influential backers, smart people and constituencies, good messengers and even a window of opportunity that allows or even invites another line of thinking, e.g. an election, an unexpected political event, new evidence or an emergency[16].

The challenge of silos, bubbles and echo chambers

Our natural emotional attachment to resolve reality in the values and frames our political brothers has been very much facilitated of late by social media that allows us to construct a world literally of all the opinions we ‘like’ and led to significant reflections the challenges of dealing with bubbles, silos and echo chambers, where we rarely hear any dissenting opinion or interpretation and encourages us to be outraged by dissent or even challenge.

The cascade of misinformation or limited information is often how the bubble is discussed. In the controlled environment, a trusted source introduces new information that sounds believable and fits a strongly held value position, if you are the next person in the chain there is significant social pressure to agree and that tends to happen quickly, and then the further down the chain we go, first you have to the holder of significantly better information and also have standing in the group to publicly disagree.

The effect of the bubble Sunstien’s experiment on conspiracy theories with a group moderate republicans and a separate group of moderate democrats asked to discuss divisive issues such as affirmative action, gay marriage. Both groups emerged from the experiment “more convinced, extreme,

While it is easy be critical about the elite nature of the public agora of opinion in the media/political landscape of the past, it was normal to hear and have to be respectful of the people delivering divergent opinions. The bubbles, silos and echo chambers of our ‘like’ worlds have changed that balance in public opinion and really accelerated the emotional attachment to a certain position and surely, make a significant contribution to the post-truth, anti-expert agenda.

This may indeed be one of the reasons we as campaigners need to be much more cognisant of the psychological and emotional dimension of the public[17].

[1] 16

[2] Lakoff, George (2004) Don’t think of an Elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. VT: Chelsea Green Publishing & Changing the Public Conversation on Social Problems: A Beginner’s Guide to Strategic Frame Analysis, E-Workshop, FrameWorks Institute 2009 http://sfa.frameworksinstitute.org/ & Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books. [we can go more on the sources here too – put in a political comms one here too] & http://www.frameworksinstitute.org/sfa/pdf/disciplinaryinfluences.pdf

[3] Calais crisis: Cameron condemned for 'dehumanising' description of migrant, The Guardian online, 30 July 2015 http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jul/30/david-cameron-migrant-swarm-language-condemned

[7] Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books. [17]

[9] http://www.ippr.org/publications/alien-nation-new-perspectives-on-the-white-working-class-and-disengagement-in-britain & https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/sunder-katwala-david-goodhart/british-dream-review-and-authors-response

[10] https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/sunder-katwala-david-goodhart/british-dream-review-and-authors-response

[11] [3]

[12] Kanneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books & https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/nyhan-reifler.pdf [21]

[13] [16] [20] [18]

[15] [16] [37]

[16] kingdon

[17] 14, 22, 1, and Sunstein conspiracy theories